By Ron Evans

About 20 years ago I discovered the music of folk legend Woody Guthrie. I was listening to some radio interview with Beck, who I was obsessed with at the time, and he mentioned that his earliest recordings were largely inspired by Woody Guthrie. This sent me on a quest to find some of Woody’s music as I love tracing the influences of my favorite artists. I was immediately charmed by the simplicity of the tunes, the catchiness of Woody’s playful yet earnest vocals and the ghostly, frozen-in-time feeling you get when listening to these scratchy, muffled, tinny songs captured in the early days of recording.

I was sort of shocked when I first heard Guthrie mention the Grand Coulee Dam in some of his lyrics but soon learned that not only did he write about the dam, he did so while he was actually up here in Washington State. And he was hired by the government to write an entire collection of songs to sell the American people on the idea of The Grand Coulee Dam and the notion of publicly owned power. It’s hard to truly express how surprising that sounded to me after learning of Guthrie’s often-polarizing politics, anti-government (in some ways) lyrics - Woody was even associated with the Communist Party, although most accounts claim this association has been somewhat exaggerated. But the biggest surprise to me was...how the hell had I never heard about this?

Around that same time, KEXP radio host Greg Vandy (The Roadhouse) had had a similar realization concerning Woody and The Grand Coulee dam. Vandy intended on getting to the bottom of this fascinating story and soon found himself working on a book (something he’d never done before) and the history he uncovered plays out like a Cohen Bros. film with a convergence of so many unlikely happenings, it hardly seems true. Yet it is. Vandy’s book, “26 Songs In 30 Days: Woody Guthrie’s Columbia River Songs and the Planned Promised Land in the Pacific Northwest” paints the picture of this ‘almost lost to time’ story in great detail. I sat down with the author for an in-depth talk about the book, the folk singer and the mighty Grand Coulee Dam.

How and when did you first fall in love with Woody Guthrie’s music and how long after that did you start researching the book?

Well, I’d say it’s more like ‘when did I begin to appreciate his music’ and understand the greater context of why he’s considered so important. Woody can be a difficult listen, and like many, I knew the name more than his songs. I made the connection that he wrote all these songs about the Columbia River Project and then one day, when I was supposed to be working, I was in the Grand Coulee Dam Visitor Center. They have this really cool little theater there, and while I was watching all the reels of historical films about the building of the dam, there was some female harmony version of “Roll On Columbia” that I’d never heard before. It’s not like there’s a lot there to recognize Woody’s contribution to the project. It sounded like a 1980’s recording and I still don’t really know who it was. But I was like, ‘oh, that’s a new version.’

At the time I was developing these theme shows on KEXP, where I take one song and play the many versions of the same song. Usually traditional songs. It makes you appreciate the song and learn about it and see the evolution of it. So I started doing that with “Roll On Columbia” and then I realized there was a whole song cycle that Woody Guthrie wrote about his experience being employed by the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA). Given this context, I understood and appreciated the songs much more. The same is true for his Dust Bowl Ballads. I became a fan like everyone else who seeks it out.

I started doing research for a special three-hour radio show, in which I interviewed some of the people with first-hand experiences with the story, including Michael Madjic (University of Oregon) who produced a video documentary on the whole thing. I aired different versions of this radio show over the years, and it landed on the ears of Sasquatch Books who offered me a deal to write a book. I started writing it in 2014.

The book sets the stage pretty early on for this collaboration between Woody and the BPA. And for unlikely as that pairing was, the stories leading up to it illustrate why it wasn’t quite as crazy as it sounds. Where do you begin to research for a book like this, which is part biographical and part historical documentation?

Well, I go from knowing that there’s this song cycle (which is on an album called The Columbia River Songs) to finding Madjic’s documentary and then producing the radio special. And then from there, after the book deal, I filled in the details with independent research with lots of help from people like Jeff Place from Smithsonian Folkways, The Woody Guthrie Archives in Tulsa and the BPA archives in Portland. Libby Burke was a godsend there.

And so through all that I picked up on the amazing story and soon realized that not much had been written about it before. At all. The two main Guthrie biographies, surprisingly, only provide a scant half dozen pages or so to the BPA story. And most people who live in this state, and in Oregon, are unaware that this happened at all, or that Woody Guthrie has an imprint here where he actually wrote songs about us, about where we live here in the Northwest. And that “Pastures of Plenty” is literally about the Columbia River Basin and a big utopian vision to solve the Dust Bowl crisis and bring electricity to rural farmers.

It’s very exciting to find out that these songs are about us and where we live. It’s like going to a museum, and you’re like ‘Oh, I can see my house in that Rembrandt.’ It’s kind of mind blowing.

The idea of writing 26 songs in 30 days is impressive on just about any level. But the fact that some of those songs ended up living on, like “Pastures of Plenty”, as icons of folk music - I think is pretty incredible.

Although Woody was known, as were most folk musicians of the time, to borrow or straight up repurpose melodies for his new songs. Talk a little bit about Woody from a songwriting standpoint.

Woody’s process as a traditional folksinger is fairly typical. And like most folksingers, he sang the old songs. And this is something that I think is lost on a lot of modern listeners, because it’s certainly an old fashioned concept. But it’s really what folk music is all about, which is not necessarily writing new songs the way the Beatles wrote The White Album. It’s more like, there are these old songs that people have always sang to each other for generations, learning from each other and from song books well before the advent of recording technology. The songs passed from person to person in what has become known as the ‘oral tradition’ where people learn songs from people actually singing the songs.

Over time the songs changed, morphed, and adapted, sometimes into whole new songs, to fit the needs of the performer and reflecting different geographies and local vernacular - where everyone has their own way of doing a popular song, his or her way. This is called the ‘folk process.’ When records happened in the late 1920’s and the first recordings by the Carter Family were released, these were old songs. Songs that A.P. Carter heard orally, from his community. He was like a collector. Then he recorded them. Woody was like this too, but Woody would write his own lyrics to existing song melodies. Again, not the first one at all. Joe Hill used and adapted old melodies for his labor songs at the turn of the 20th Century as did other protest singers. The idea being that if you knew the melody already you could follow the song easier. That whole thing is really fascinating to me - ‘the folk process.’ That’s what Woody Guthrie did. Nobody owned the old traditional songs. Still don’t.

So yes, Woody adapted old songs to fit his needs all the time.

Grand Coulee Dam mid-construction in 1939 - Photo/Bonneville Power Administration

The idea of the Grand Coulee Dam was thought to be a pipe dream by most people. Just a thing too impossible to imagine or even justify. But one early visionary and champion for the project is a prominent name here in Wenatchee. Publisher of the Wenatchee Daily World, Rufus Woods. How important was Woods’ support for the project of the dam in getting things off the ground?

It was huge, because he was the ultimate booster. And it’s a little bit complicated as to what he wanted versus what ultimately happened, as he was for private interest and for making the whole project a private enterprise. The federal government at the time, however, was all for public power and for public ownership. So there’s a difference there. But Rufus was great, because he made it really sort of an entertaining story about how the little guy was gonna win over the big guy, and the Grand Coulee Dam is gonna help the community and bring a better life to the Wenatchee area.

Understanding that time and place is so interesting and so important because they had these movie reels that played in all the cinemas back in the day. When you’d go see a movie you’d see the main feature, then you can maybe see a short and then there’s always a newsreel in there too. The story of the Grand Coulee Dam was a popular feature in these reels. This is before TV sets of course. And I think it was really fun and encouraging for people who were living through the Great Depression to know that there is a sense of progress going on. And I think that’s why it was such a popular story because not only was it the biggest thing that man had ever done in the middle of nowhere, but it was a sign of America coming back from the Depression.

Along that propaganda line, there were plenty of people that were sort of scoffing at Woody Guthrie, his lyrics for these songs and his involvement with the dam in general as little more than propaganda, which I suppose, by definition is propaganda. Or do you see it differently?

Well, yeah, I think it’s classic propaganda but as I wrote in the book, it was also “public relations for The People.” That’s how Harry Hopkins put it (Roosevelt’s WPA Director). He said, “it’s about time people have propaganda for them. The big power companies spend millions on propaganda for private utilities.”

And I think that’s what this was - it was propaganda to educate people that public power was something that was viable and possible, and that we didn’t need private interest to charge whatever they wanted for power from rivers that belong to everyone, because they are our natural resource. The project was aimed at improving the lives of common people by bringing electricity at a low rate to people in rural eastern Washington and Oregon for the first time. Literally bringing people out of the dark and providing a more modern lifestyle for everyone. It was part of The New Deal, and yes, it needed to be sold by a folksinger because this was actually our first folk revival, back in the 1930’s. A new American narrative featuring working people that was both organic and fully sponsored by the Roosevelt administration to promote New Deal policy. It’s quite fascinating.

Plenty of artists or celebrities have cashed in on a paycheck to promote something or another. But a major difference here is that it seems to me that Woody truly believed in this project.

He needed a job really bad as I explained in the book. He was at probably his lowest ebb, ever. He was discouraged. He was broke. He had a family and needed a gig, and this was a great gig. But this wasn’t selling a bar of soap or a brand of cars. It was about a whole ideology of public or private. About public utility districts providing energy and power to people who didn’t have it before and irrigating dry dusty land for people in order to create something for themselves. A cure for the Dust Bowl and a place for migrants to settle down. So, yes, he was way into it. We make reference in the book that Mary, his wife at the time, said that Woody would come home super jazzed about the whole thing and he was inspired. That’s clearly evident in the quality of the songs. It was the perfect job for him. And he loved it. He loved this area too. I mean, think of how pristine and beautiful the Pacific Northwest was back in 1941. I think being from the Dust Bowl region, the lush landscape made a lifelong impression on him.

“Roll On Columbia” was a song that we actually learned in grade school by heart. I don’t remember Woody Guthrie’s name ever being associated with it. It was one of those songs that just was. In fact, the song itself was famous before Woody’s recording of it was released. How does that even happen?

So this is one of the most amazing discoveries and most interesting aspects of the book for me. The fact that the most well known Woody Guthrie song from this song cycle was never recorded by Woody Guthrie. For years people thought it was never recorded by him. Now, this goes back to the idea that songwriters published songs in song books back in the day and that Woody wrote a million songs but only got a chance to record a fraction of them. And of the 26 songs we reference in the book, only 17 of those songs had been recorded. So it’s not too crazy to think that we know “Roll On Columbia” from other artists, or from summer camps or school via a song book.

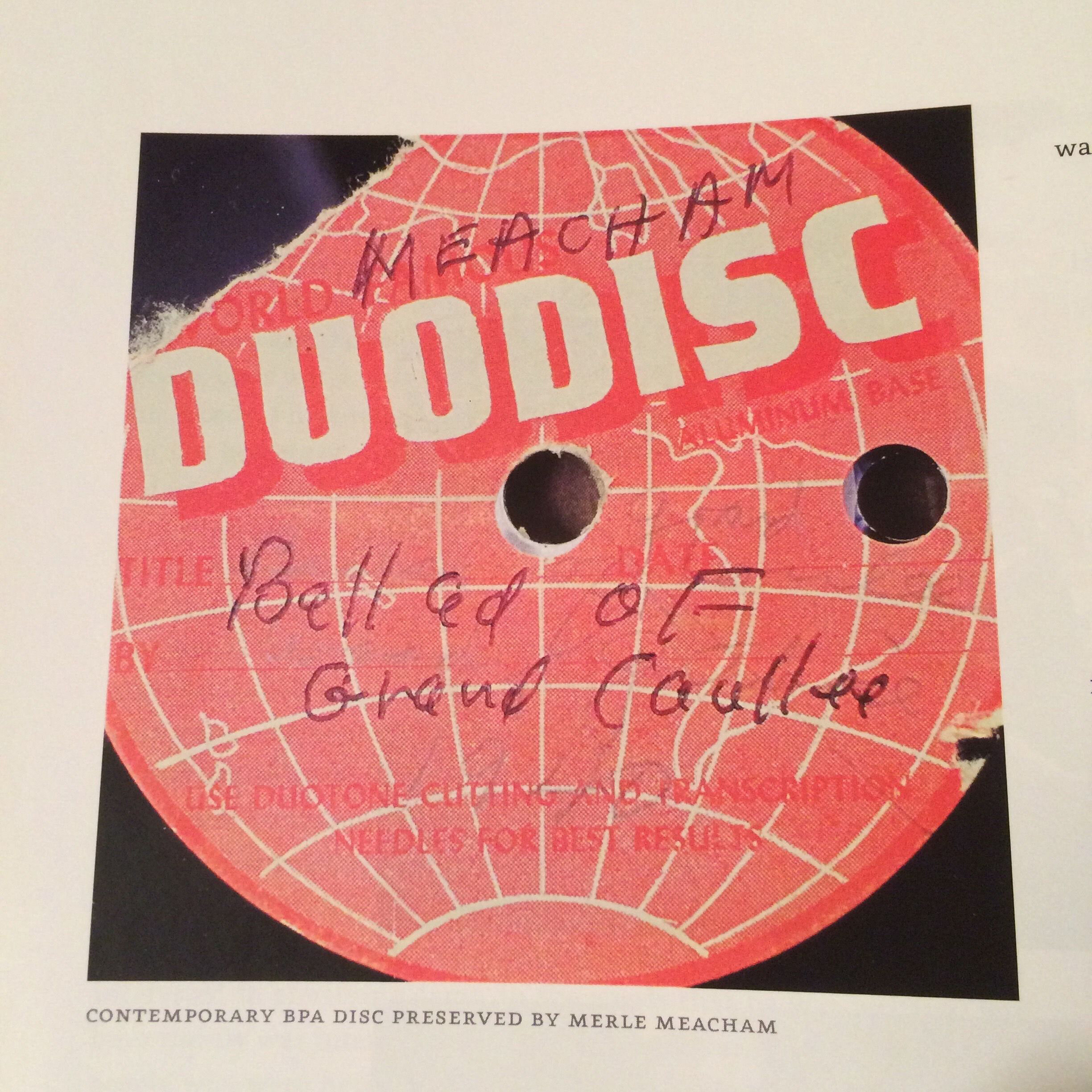

Treasure in the closet. Unearthed acetate of Woody’s BPA recordings.

It wasn’t until 1987 that anyone heard a recording of it by Woody Guthrie. It was Bill Murlin of the BPA who discovered the old acetate when he made contact with retired BPA employees via an internal newsletter. And there were others too; all these lost acetates that Woody Guthrie recorded in the BPA basement as demos were found in private hands. I imagine this make-shift studio closet where he banged out these songs during his month-long employment there. And one of the lost recordings was “Roll On Columbia!” It’s pretty amazing and I imagine it blew the minds of hard-core Guthrie fans when it was discovered.

There are actually 12 songs that came out of the woodwork from surviving, physical acetate copies which were in the possession of old BPA employees. And of the 26 songs that Woody wrote for his Columbia River song cycle, he recorded 5 of them later, commercially, for Moe Asch for his Folkways label in 1944, and those are the songs we know, like “Talking Columbia”, “Hard Traveling”, “Grand Coulee Dam” etc. Apparently, Woody forgot about “Roll On Columbia” by then. We try to explain that in the book. The whole story has one amazing thing after another.

It blows my mind that Woody was recording in the basement of the BPA. I suppose it’s too much to hope for some sort of preservation, or memorialization of that auspicious occasion.

The BPA moved out of their original building, and I doubt anything was preserved there. I’m not even sure the structure still stands.

Another aspect of the dam that I don’t remember ever being taught in school was the devastation that the project had on the indigenous people of the area. Talk a bit about that and how it led to the Ceremony of Tears.

Whenever we talk about the Grand Coulee Dam there are two sides of that tale. In the introduction of the book we give a full disclaimer to inform the reader that this is a story about Woody Guthrie, and how this whole thing came about. And you have to keep in mind that while we tell the story, there’s a whole other side to it that’s terrible. The over-damming of the Columbia, turning this natural, beautiful river into a lake is a terrible consequence, environmentally. And the consequence of the Coulee Dam for Native Americans is the loss of salmon, lifestyle, and culture. And they received none of the power or electricity, even though the reservation is literally on the other bank of the river. The whole story is really ridiculous. The best book that I’ve read about this angle of the story is called “A River Lost” by Blaine Harden. He explains how arrogant it was to not consider anyone in this equation other than white males. So that’s a fact you have to know going into telling a story like this.

The Ceremony of Tears was this moment in time when the native tribes were realizing their fate and that the Columbia River was going to be dammed, and that the river was going to rise. And that not only were the salmon going to be blocked, a lot of the land would be covered with water, including burial sites. The ceremony was sort of a solemn acknowledgement that things were going to change at that moment for them. And not for the best, obviously.

Poster for the epic Woody Guthrie Day event at Grand Coulee Dam in 2016.

In 2016, you organized something that I had been waiting for for a long time, even if I didn’t know it. Woody Guthrie Day at Grand Coulee Dam. An all day event with live music, film screenings, panels and Woody-centric exhibits. How did that all come together? And was this a one off? Or are there plans for maybe future Woody celebrations?

Oh, yeah, definitely a one-off. It was meant to finally recognize Woody Guthrie at the Grand Coulee Dam, which they really never had done before. Which kind of surprised me and kind of blows my mind in a certain way that a guy as famous as Woody Guthrie who wrote a song called “Grand Coulee Dam” is not fully recognized at the Grand Coulee Dam. I felt like, you know, 75 years after the fact it would be nice to have some sort of recognition of those songs and the guy who wrote them. Granted, there is a display of him in the Visitor Center with a xylophone thing where you can play “Roll On Columbia”, but it’s easy to miss. My book was timed to come out on the 75th anniversary of Guthrie’s employment with the BPA, so we partnered up with the Bureau Of Reclamation to do the event. They were pretty cooperative in helping us out.

We had Deana McCloud come out from the Woody Guthrie Center (in Tulsa), which was really flattering. Bill Murlin and Libby Burke were there from the BPA, and we had these great panels, which I think was the best part of the event, in that little theater. And of course we had singers and some bands. I really envisioned a whole big stage and a grandstand and Arlo Guthrie playing, but you know, we really couldn’t get that together. There was no budget at all. Everyone did it because they wanted to be there. The location is so remote that it was hard to get Seattle people to drive all the way out there. But it’s a special place in the Coulee Corridor, and I recommend it to anyone looking for a gorgeous road trip.

When I first learned about Woody’s time up here with the Columbia River songs, I hit the road. I was on a quest to see the dam with renewed interest. I was also looking for any little roadside marker - some sort of attraction or mention of Woody that I could find, only to discover there was no such thing. Except for a little power substation they named after him - you know, one of those eyesore things that we all try to hide with fences and shrubs - somewhere down on the Oregon-Washington border, which is such a touching tribute.

Your book really helps the story come back into light. But why do you think it ever faded to begin with? And why do you think these acetates ended up under the bed of some dude that just never really thought about it until someone brought it up decades later?

I don’t think anyone even knew what really happened until the 60’s. We mentioned in the book that there was a writer for the AP who sort of pieced it together for the first time in a news story. The original documentary film, “The Columbia”, that Woody was hired to write songs for eventually materialized but not until after the war, in 1949. By that time, it wasn’t very relevant and nobody actually saw the film. After World War II the country immediately shifted its focus to a more urban economy and the agrarian utopia featuring a Planned Promised Land was already out-of-date and not realistic.

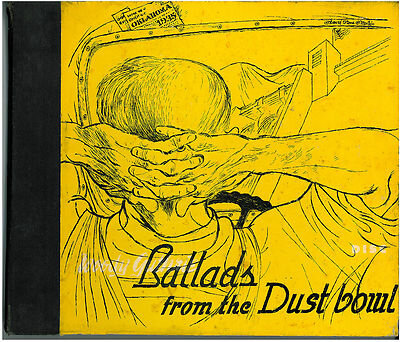

The rare, earliest Columbia River songs compilation by Moe Asch - oddly attributed to the Dust Bowl ballads in spite of the fact that the man in the illustration is clearly parked in front of the Grand Coulee Dam, as spotted by Vandy.

So not many people know this happened, even to this day. The five songs released commercially were heard much later, and music fans referred to these songs as “Woody’s dam songs” or his “Columbia River songs”, but not many knew that there were 17 other songs until Murlin produced the Columbia River Songs album in 1987 with all the unknown recordings. However, another prized nugget of my research uncovered an album that Moe Asch released in 1948, which was actually the first Columbia River songs album, with many of the songs we are talking about here, but for some reason Asch called it Ballads From The Dust Bowl. It’s weird because it had only one Dust Bowl song and all the other songs were Columbia River songs. So I assume that Asch was just using the tried and true Dust Bowl brand to sell the record. But the cover is a man reclining in his car driver seat looking at the Grand Coulee Dam. Nobody made this connection before, and when I called Jeff Place at Smithsonian about it, he agreed. It’s a pretty rare record. So that’s always funny to me.

One of the things I always thought would be amazing on a road trip of that region would be some sort of ‘Woody sat and strummed his guitar here’ roadside markers overlooking the river. A man named Elmer Bueller was tasked by the BPA to drive Woody around and basically do just that. Take in the sights, smell the fresh Columbia River air and write songs. You once interviewed Bueller about his time with Woody. How does he recall this experience?

Yeah, I called him on the phone back when I was working on the radio show documentary for KEXP, probably around 2006, maybe? Just a few years before he passed away. He was a very elderly man and just a great guy to talk with about his experience - you know, having someone with first-hand experience at whatever you are researching is so valuable. Especially to someone like Woody Guthrie, which was pretty exciting. There are really not many people you can say that had first hand experience with him or with this whole story. Besides his stories, I wanted to know what the route was from Portland to Grand Coulee and back when they drove it in a government car - a brand new 1940 Hornet Hudson. And that way I could make a map and do what you’re saying, visualize Woody Guthrie singing over the river or whatever he did, and share the romance of that vision. Also, to make a definitive timeline because Woody only worked on this job for 30 days.

But, I just could not get him to nail it down. Of course he was 90 years old and this happened so long ago for him, but I was hoping for some sort of logbook, you know. When you work for the state or for the federal government everything is written down, so I thought there might be a surviving journal or log book or something like that. But the best I could get from him, which I wrote in the book, was they started going east on the Columbia and through the towns of Dee, Parkdale and eventually to The Dalles. There’s a story about a stop-over in Arlington, and a quick side trip to Lost Lake, which apparently blew Woody’s mind. He said something like, “I’m in paradise.” This was before the interstate highway so they were taking all these older roads and they cut up somewhere before Walla Walla, then north east to Spokane, and then from Spokane to Grand Coulee and from Grand Coulee they followed the river down to Portland. So that’s the route as best as I can tell. Speaking with Elmer was one of my favorite parts of the research.

Bueller once claimed to have heard Guthrie strumming his guitar in the backseat on one of these drives throughout the region. And apparently he was working and reworking lyrics to a song that hadn’t been recorded yet. A little tune called “This Land Is Your Land.” This isn’t one of the official Columbia River ballads, but is it fair to at least imagine that Woody might have been influenced by his time here in writing one of the most famous songs in US history?

Well, Woody definitely wrote that in 1940 in New York, but didn’t record it until 1944 with Moe Asch. Like I mentioned before, writing a song and recording a song are two different things, and back then Woody would record a whole batch of songs on a whim, then Asch would release them whenever, and as he saw fit. Folkways was a very small indie label, and most of the recordings Woody made back in the 40’s are on albums that came out in the 50’s and 60’s or his songs were made popular by other singers, like Pete Seeger. The Folk Revival of that time is how most people discovered Woody Guthrie’s songs, but ironically he was too sick (with Huntington’s disease) to play and participate in that new scene. That’s how the legend of Guthrie really began, in that people knew these songs that were written much earlier but he was a man of mystery to kids in the early 60’s folk revival scene. But he very well could have been still working on it and just singing it, or maybe changing it, who knows? I think “Pastures of Plenty” is just as important as “This Land Is Your Land” and it’s really the same kind of song in how ‘this land’ belongs to you and me, and the private versus public space argument. It’s the ultimate migrant song.

What we did discover about that song (Pastures), and Libby Burke has a lot to do with this, is that we know for a fact that Steve Khan, the guy that hired him at the BPA to write songs for his film gave Woody a copy of the book The Grapes of Wrath. Khan gave him a bunch of materials for Guthrie to bone up on the history of the area and the meaning of the project. So we think that he was reading The Grapes of Wrath with Elmer Bueller during those rides and that the book was really influential in writing “Pastures of Plenty.” And I figured out that Woody Guthrie had never read it before, even though he’d written a song about the lead character, Tom Joad. But he’d seen the movie. The Grapes of Wrath was published in 1939. John Houston’s movie came out in 1940, which is a pretty quick turnaround for a movie of that magnitude. But I found this audio recording from December of 1940, five months before heading to Portland, where Woody was performing with Leadbelly in New York City, and in between songs Woody says, “Oh, here’s a song called ‘Tom Joad’. I haven’t read the book. But I saw the movie!”

On the topic of your book, as a radio personality and an author the obvious question, I suppose: Did you think about doing an audio book version? Or is that something possibly on the horizon?

Well, I talked to the publisher about that. I thought that’d be something great to do back then. But it was a question of cost considering you need the rights to the song recordings in addition to the rights to print the lyric manuscripts. It’s all very expensive.

There’s a company called TRO, The Richmond Organization that owns all the publishing for Woody Guthrie. And they were pretty hard to deal with. So for the audio recording, I think it would be cost prohibitive for any publisher to pay for those to use in an audio book. Who knows, I had my hands full just writing the book with my co-author, Dan Person.

I think a lot of people are surprised that Woody Guthrie isn’t in the public domain.

There’s so much to say about that. Public domain is about 1925, I think. But for this situation and for the sake of argument, when you write songs for the government you’re being paid for by the government - which is us. So really, don’t we own the songs? But to have that discussion with the rights holders... you may as well just forget about it. The other thing to say is I would never object to any copyright that Guthrie and the family lays claim to because the fact is, Woody Guthrie never really got paid. He was scraping and struggling his entire life and he got hardly any royalties from anything. When The Weavers did some of his songs he got paid a little bit, but it was far too little far too late. When Woody passed, a lot of the publishing rights served a great purpose in helping his family. So there’s no beef from me.

Are there any other subjects that interest you enough to pursue a book? Or is this one good for you?

You know, in both Woody Guthrie biographies, there’s only like four to seven pages dedicated to this amazing, incredible story. So I’m very proud that we - me and Daniel Person, told the story, finally. And it’s a great story. I love the story. But, I wouldn’t call myself a dedicated author. This whole story, in a way, chose me.

That was a while ago now, and considering I have kids and zero time, it’s hard to imagine doing another heavy lift - because the money just isn’t there. But to answer your question, the whole weird story of local hero Harry Smith would be a good one to explore. He’s the guy behind the Anthology Of American Folk Music and he’s from my hometown of Bellingham. He’s a very complicated figure, so I’m assuming that’s why no one has chased that dragon. Maybe someday!

Final Note: After reading this you may just want to load up the car, pop in some Woody Guthrie and head out on a road trip to the Grand Coulee Dam. Unfortunately the visitor center is closed due to Covid but the park and the main vista points are all open so you can take in the vast views of this seemingly impossible monument of human ingenuity. Breathe in the fresh air of that ‘misty crystal glitter’ as the waters slide down the spillway and think about the culture, politics, dreams and hardships the Grand Coulee Dam represents. However you feel about this controversial creation, I think we can all agree that it might just be the biggest thing that man has ever done.

Woody Guthrie “killing” fascists in 1943 - photo by Al Aumuller